1 Introducing Go

1.1 Solving modern programming challenges with Go

1.1.2 Concurrency

- Channels help to enforce the pattern that only one goroutine should modify the data at any time.

- … channels are used to send data between several running goroutines.

2 Go quick-start

2.2 Main package

- If your

mainfunction doesn’t exist in packagemain, the build tools won’t produce an executable._ "github.com/goinaction/code/chapter2/sample/matchers" - The blank identifier allows the compiler to accept the import and call any

initfunctions that can be found in the different code files within that package. - All

initfunctions in any code file that are part of the program will get called before themainfunction. - By default, the logger is set to write to the

stderrdevice.

2.3 Search package

2.3.1 search.go

- The compiler will always look for the packages you import at the locations referenced by the GOROOT and GOPATH environment variables.

- In Go, identifiers are either exported or unexported from a package. An exported identifier can be directly accessed by code in other packages when the respective package is imported. These identifiers start with a capital letter. Unexported identifiers start with a lowercase letter and can’t be directly accessed by code in other packages. But just because an identifier is unexported, it doesn’t mean other packages can’t indirectly access these identifiers. As an example, a function can return a value of an unexported type and this value is accessible by any calling function, even if the calling function has been declared in a different package.

- In Go, all variables are initialized to their zero value. For numeric types, that value is

0; for strings it’s an empty string; for Booleans it’sfalse; and for pointers, the zero value isnil. - … short variable declaration operator (:=). This operator is used to both declare and initialize variables at the same time.

- The short variable declaration operator is just a shortcut to streamline your code and make the code more readable. The variable it declares is no different than any other variable you may declare when using the keyword

var. - A good rule of thumb when declaring variables is to use the keyword

varwhen declaring variables that will be initialized to their zero value, and to use the short variable declaration operator when you’re providing extra initialization or making a function call. - When we use

for rangeto iterate over a slice, we get two values back on each iteration. The first is the index position of the element we’re iterating over, and the second is a copy of the value in that element. - When you have a function that returns multiple values, and you don’t have a need for one, you can use the blank identifier to ignore those values. In our case with this range, we won’t be using the index value, so the blank identifier allows us to ignore it.

- Use the keyword

goto launch and schedule goroutines to run concurrently. - In Go, all variables are passed by value. Since the value of a pointer variable is the address to the memory being pointed to, passing pointer variables between functions is still considered a pass by value.

- The anonymous function isn’t given a copy of these variables; it has direct access to the same variables declared in the scope of the outer function.

2.3.2 feed.go

- The keyword

deferis used to schedule a function call to be executed right after a function returns. It’s our responsibility to close the file once we’re done with it. By using the keyworddeferto schedule the call to theclosemethod, we can guarantee that the method will be called. This will happen even if the function panics and terminates unexpectedly. The keyworddeferlets us write this statement close to where the opening of the file occurs, which helps with readability and reducing bugs.

2.3.3 match.go/default.go

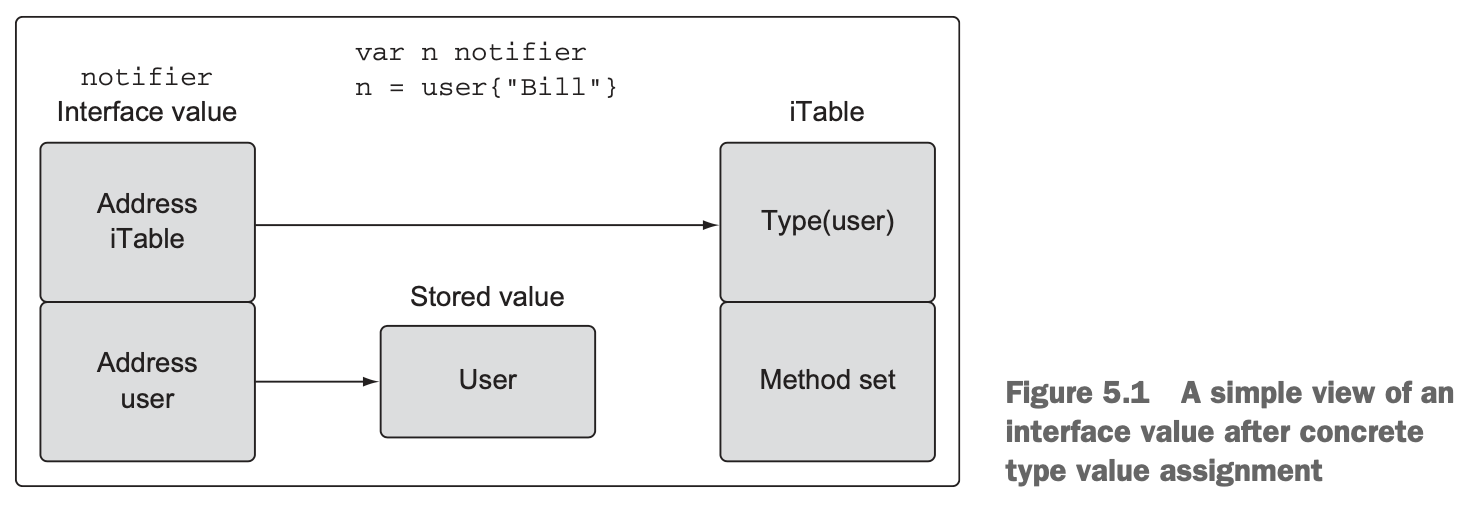

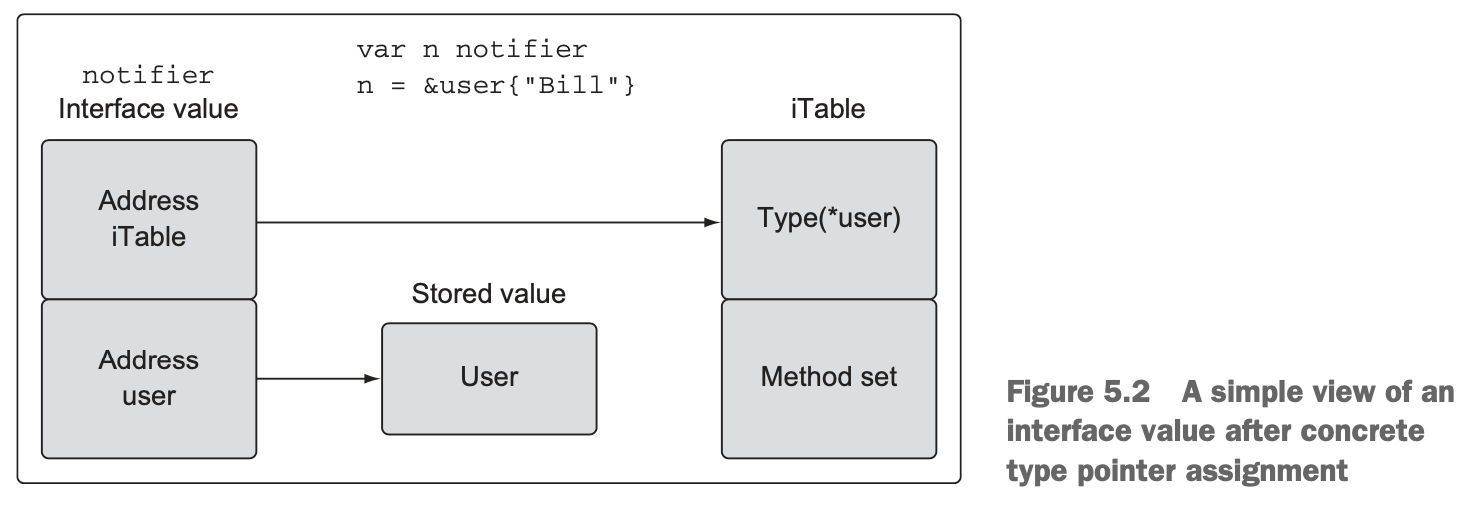

- Example of interface method call restrictions:

// Method declared with a pointer receiver of type defaultMatcher

func (m *defaultMatcher) Search(feed *Feed, searchTerm string)

// Call the method via an interface type value

var dm defaultMatcher

var matcher Matcher = dm // Assign value to interface type

matcher.Search(feed, "test") // Call interface method with value> go build

cannot use dm (type defaultMatcher) as type Matcher in assignment// Method declared with a value receiver of type defaultMatcher

func (m defaultMatcher) Search(feed *Feed, searchTerm string)

// Call the method via an interface type value

var dm defaultMatcher

var matcher Matcher = &dm // Assign pointer to interface type

matcher.Search(feed, "test") // Call interface method with pointer> go build

Build Successful- There’s nothing else that the

defaultMatchertype needs to do to implement the interface. From this point forward, values and pointers of typedefaultMatchersatisfy the interface and can be used as values of typeMatcher. That’s the key to making this work. Values and pointers of typedefaultMatcherare now also values of typeMatcherand can be assigned or passed to functions accepting values of typeMatcher.

3 Packaging and tooling

3.2 Imports

- If Go was installed under /usr/local/go and your

GOPATHwas set to /home/myproject:/home/mylibraries, the compiler would look for thenet/httppackage in the following order:/usr/local/go/src/pkg/net/http —— This is where the standard library source code is contained. /home/myproject/src/net/http /home/mylibraries/src/net/http

3.2.2 Named imports

BLANK IDENTIFIERThe _ (underscore character) is known as theblank identifierand has many uses within Go. It’s used when you want to throw away the assignment of a value, including the assignment of an import to its package name, or ignore return values from a function when you’re only interested in the others.

3.5 Going farther with Go developer tools

3.5.1 go vet

- It’s a great idea to get in the habit of running

go veton your code base before you commit it to a source repository.

3.5.3 Go documentation

- To start your own documentation server, type the following command into a terminal session:

godoc -http=:6060

3.6 Collaborating with other Go developers

3.6.1 Creating repositories for sharing

- A common mistake that new Go developers make is to create a

codeorsrcdirectory in their public repository. Doing so will make the package’s public import longer. Instead, just put the package source files at the root of the public repository.

3.7 Dependency management

3.7.2 Introducing gb

- One thing to note: a gb project is not compatible with the Go tooling, including

go get. Since there’s no need forGOPATH, and the Go tooling doesn’t understand the structure of a gb project, it can’t be used to build, test, or get. Building and testing a gb project requires navigating to the$PROJECTdirectory and using the gb tool.

4 Arrays, slices, and maps

4.1 Array internals and fundamentals

4.1.2 Declaring and initializing

- Once an array is declared, neither the type of data being stored nor its length can be changed. If you need more elements, you need to create a new array with the length needed and then copy the values from one array to the other.

- Declaring an array initializing specific elements:

// Declare an integer array of five elements.

// Initialize index 1 and 2 with specific values.

// The rest of the elements contain their zero value.

array := [5]int{1: 10, 2: 20}4.1.3 Working with arrays

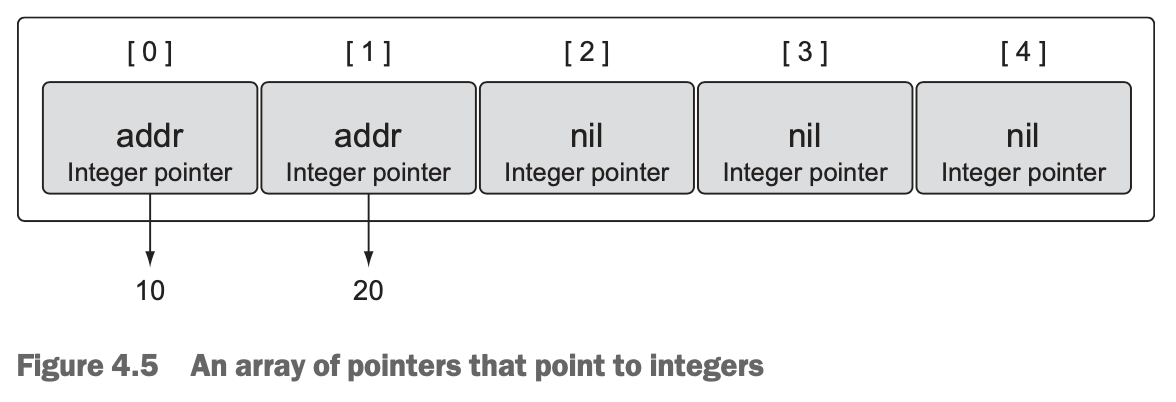

- Accessing array pointer elements:

// Declare an integer pointer array of five elements.

// Initialize index 0 and 1 of the array with integer pointers.

array := [5]*int{0: new(int), 1: new(int)}

// Assign values to index 0 and 1.

*array[0] = 10

*array[1] = 20- The values for the array declared in listing 4.6 will look like figure 4.5 after the array operations are complete.

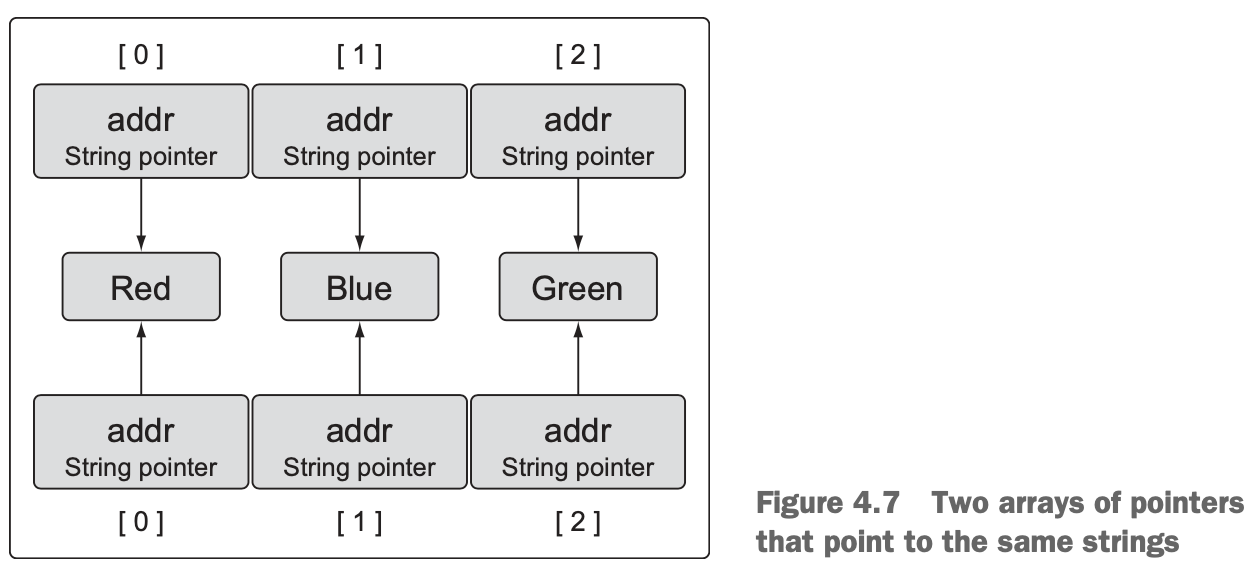

- Assigning one array of pointers to another:

// Declare a string pointer array of three elements.

var array1 [3]*string

// Declare a second string pointer array of three elements.

// Initialize the array with string pointers.

array2 := [3]*string{new(string), new(string), new(string)}

// Add colors to each element

*array2[0] = "Red"

*array2[1] = "Blue"

*array2[2] = "Green"

// Copy the values from array2 into array1.

array1 = array2- After the copy, you have two arrays pointing to the same strings, as shown in figure 4.7.

4.1.5 Passing arrays between functions

- Passing an array between functions can be an expensive operation in terms of memory and performance. When you pass variables between functions, they’re always passed by value. When your variable is an array, this means the entire array, regardless of its size, is copied and passed to the function.

4.2 Slice internals and fundamentals

4.2.1 Internals

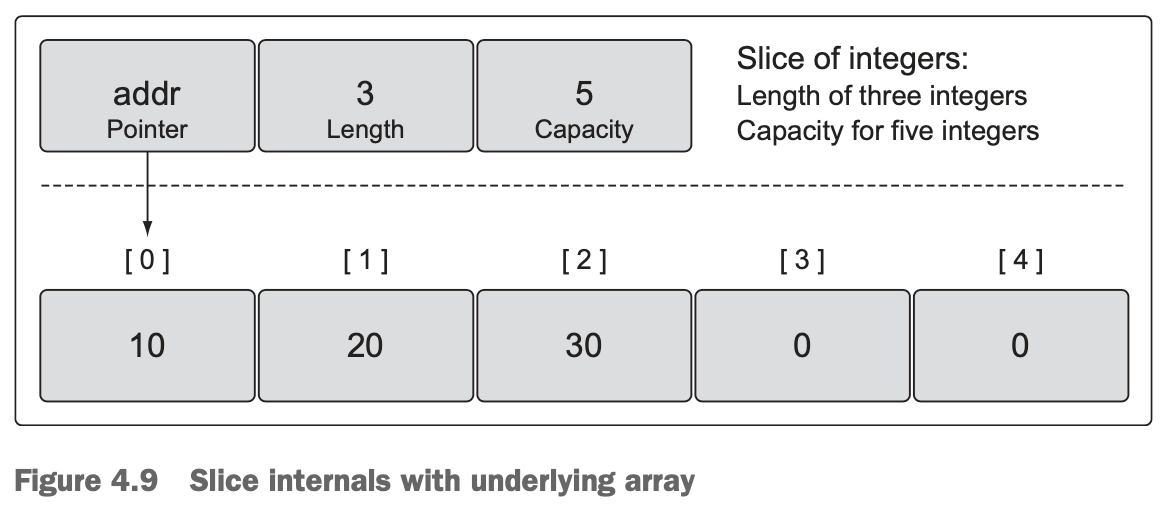

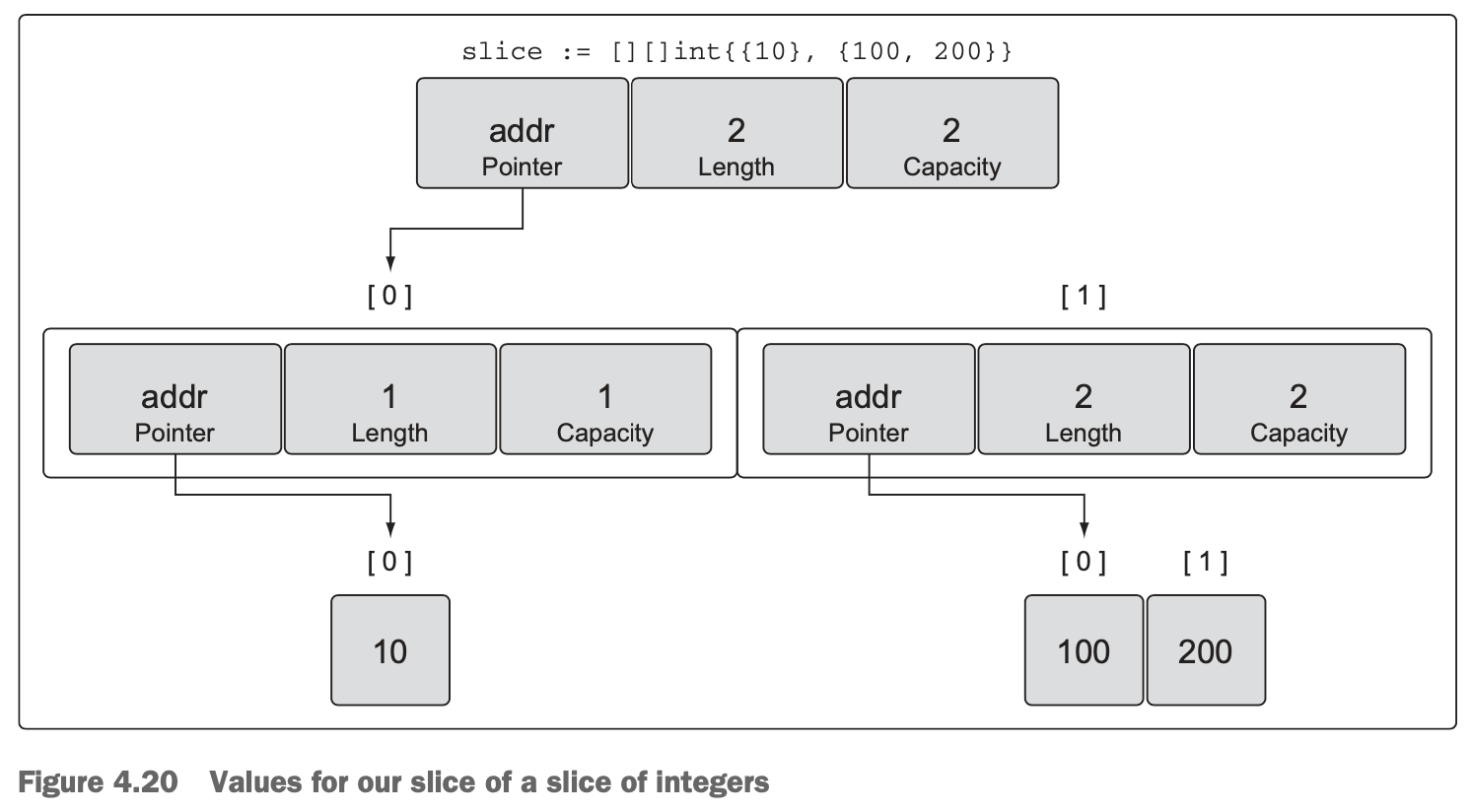

- They’re three-field data structures that contain the metadata Go needs to manipulate the underlying arrays (see figure 4.9).

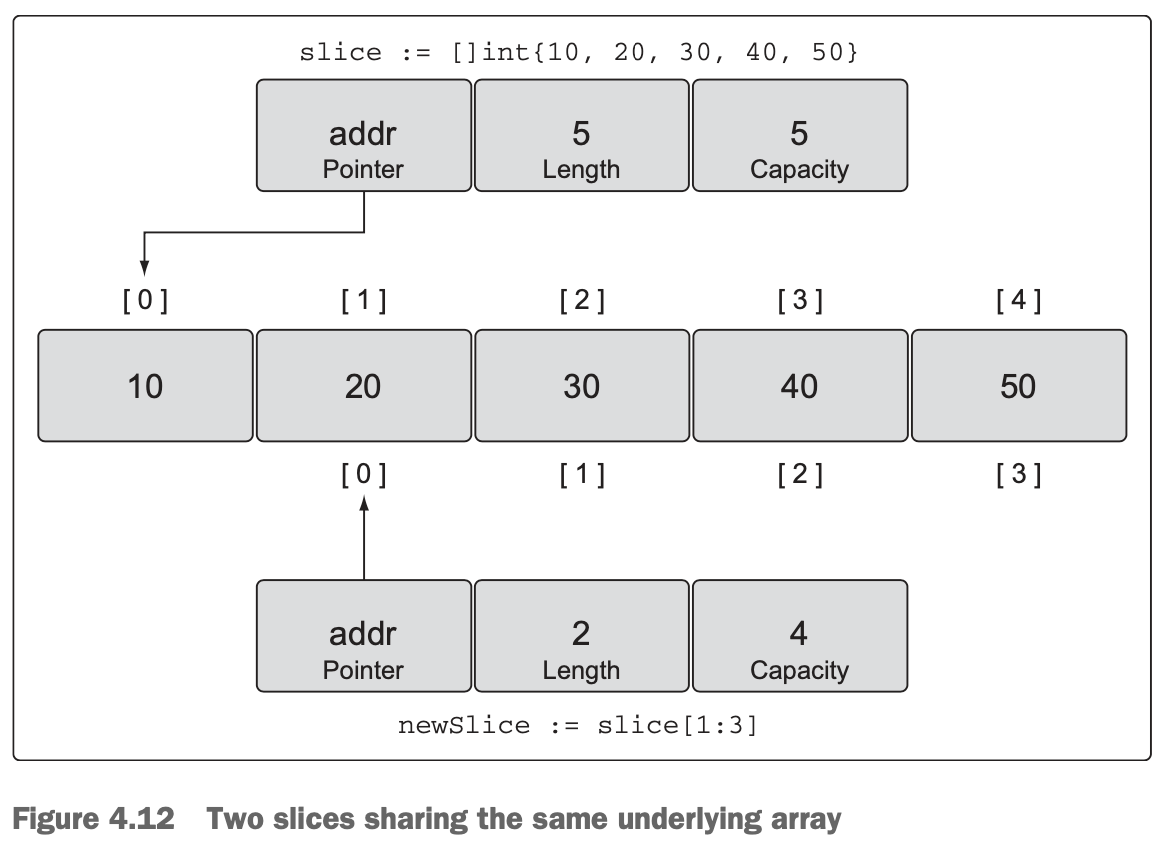

- The three fields are a pointer to the underlying array, the length or the number of elements the slice has access to, and the capacity or the number of elements the slice has available for growth.

4.2.2 Creating and initializing

- Declaring a slice of strings by length:

// Create a slice of strings.

// Contains a length and capacity of 5 elements.

slice := make([]string, 5)- Declaring a slice of integers by length and capacity:

// Create a slice of integers.

// Contains a length of 3 and has a capacity of 5 elements.

slice := make([]int, 3, 5)- An idiomatic way of creating a slice is to use a slice literal. It’s similar to creating an array, except you don’t specify a value inside of the

[ ]operator. The initial length and capacity will be based on the number of elements you initialize. - Declaring a slice with a slice literal:

// Create a slice of strings.

// Contains a length and capacity of 5 elements.

slice := []string{"Red", "Blue", "Green", "Yellow", "Pink"}- Declaring a slice with index positions:

// Create a slice of strings.

// Initialize the 100th element with an empty string.

slice := []string{99: ""}- Remember, if you specify a value inside the

[ ]operator, you’re creating an array. If you don’t specify a value, you’re creating a slice. - Declaration differences between arrays and slices:

// Create an array of three integers.

array := [3]int{10, 20, 30}

// Create a slice of integers with a length and capacity of three.

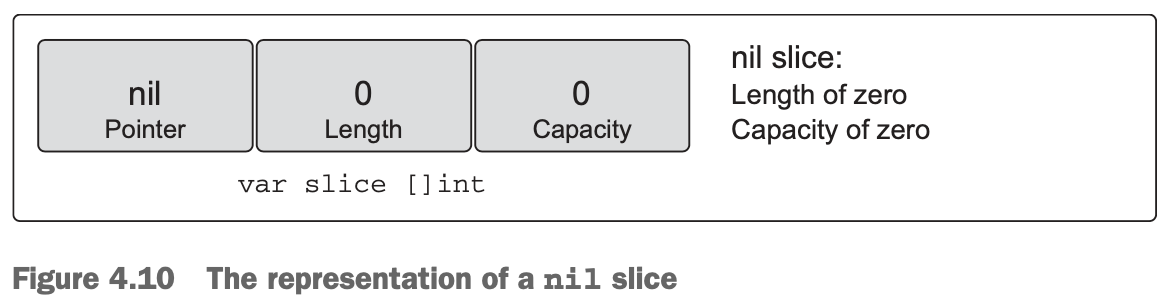

slice := []int{10, 20, 30}- Declaring a nil slice:

// Create a nil slice of integers.

var slice []int- They’re useful when you want to represent a slice that doesn’t exist, such as when an exception occurs in a function that returns a slice (see figure 4.10).

- Declaring an empty slice:

// Use make to create an empty slice of integers.

slice := make([]int, 0)

// Use a slice literal to create an empty slice of integers.

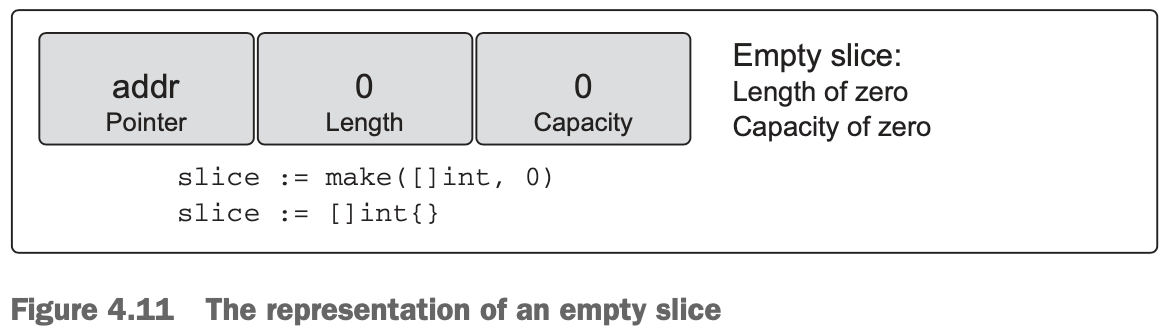

slice := []int{}- An empty slice contains a zero-element underlying array that allocates no storage. Empty slices are useful when you want to represent an empty collection, such as when a database query returns zero results (see figure 4.11).

4.2.3 Working with slices

- Calculating the length and capacity for any new slice is performed using the fol lowing formula.

- How length and capacity are calculated:

For slice[i:j] with an underlying array of capacity k

Length: j - i

Capacity: k - i- You need to remember that you now have two slices sharing the same underlying array. Changes made to the shared section of the underlying array by one slice can be seen by the other slice.

- A slice can only access indexes up to its length. Trying to access an element outside of its length will cause a runtime exception. The elements associated with a slice’s capacity are only available for growth. They must be incorporated into the slice’s length before they can be used.

- One of the advantages of using a slice over using an array is that you can grow the capacity of your slice as needed.

- The

appendfunction will always increase the length of the new slice. The capacity, on the other hand, may or may not be affected, depending on the available capacity of the source slice. - The

appendoperation is clever when growing the capacity of the underlying array. Capacity is always doubled when the existing capacity of the slice is under 1,000 elements. Once the number of elements goes over 1,000, the capacity is grown by a factor of 1.25, or 25%. This growth algorithm may change in the language over time. - The built-in function append is also a variadic function. This means you can pass multiple values to be appended in a single slice call. If you use the … operator, you can append all the elements of one slice into another.

- Appending to a slice from another slice:

// Create two slices each initialized with two integers.

s1 := []int{1, 2}

s2 := []int{3, 4}

// Append the two slices together and display the results.

fmt.Printf("%v\n", append(s1, s2...))

Output:

[1 2 3 4]- The keyword

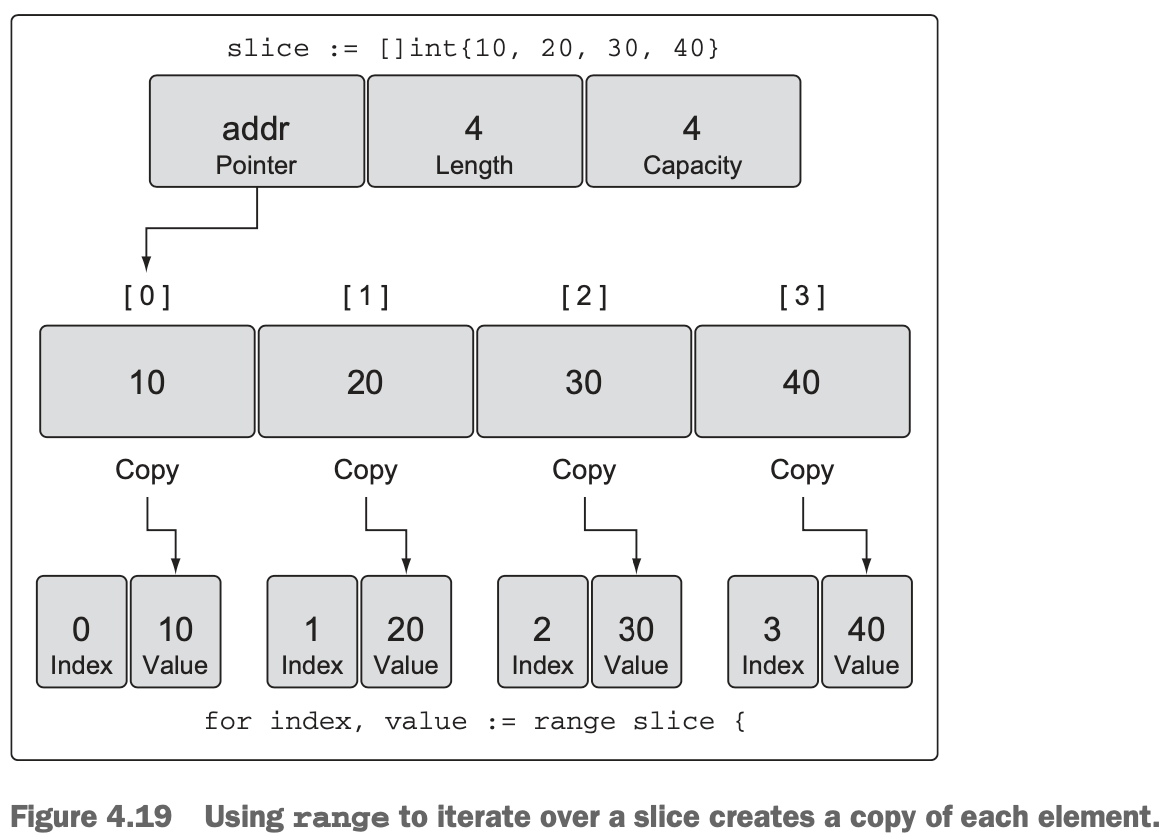

range, when iterating over a slice, will return two values. The first value is the index position and the second value is a copy of the value in that index position (see figure 4.19).

- It’s important to know that range is making a copy of the value, not returning a reference. If you use the address of the value variable as a pointer to each element, you’ll be making a mistake.

- There are two special built-in functions called

lenandcapthat work with arrays, slices, and channels. For slices, thelenfunction returns the length of the slice, and thecapfunction returns the capacity.

4.2.4 Multidimensional slices

- … slices are cheap and passing them between functions is trivial.

4.2.5 Passing slices between functions

- Passing a slice between two functions requires nothing more than passing the slice by value. Since the size of a slice is small, it’s cheap to copy and pass between functions.

- On a 64-bit architecture, a slice requires 24 bytes of memory. The pointer field requires 8 bytes, and the length and capacity fields require 8 bytes respectively.

- Only the slice is being copied, not the underlying array …

4.3 Map internals and fundamentals

4.3.1 internals

- Even if you store your key/value pairs in the same order, every iteration over a map could return a different order. This is because a map is implemented using a hash table …

4.3.2 Creating and initializing

- Declaring a map using make:

// Create a map with a key of type string and a value of type int.

dict := make(map[string]int)

// Create a map with a key and value of type string.

// Initialize the map with 2 key/value pairs.

dict := map[string]string{"Red": "#da1337", "Orange": "#e95a22"}- The map key can be a value from any built-in or struct type as long as the value can be used in an expression with the == operator. Slices, functions, and struct types that contain slices can’t be used as map keys. This will produce a compiler error.

4.3.3 Working with maps

- Retrieving a value from a map and testing existence.

// Retrieve the value for the key "Blue".

value, exists := colors["Blue"]

// Did this key exist?

if exists {

fmt.Println(value)

}- Iterating over a map using for range:

// Create a map of colors and color hex codes.

colors := map[string]string{

"AliceBlue": "#f0f8ff",

"Coral": "#ff7F50",

"DarkGray": "#a9a9a9",

"ForestGreen": "#228b22",

}

// Display all the colors in the map.

for key, value := range colors {

fmt.Printf("Key: %s Value: %s\n", key, value)

}4.3.4 Passing maps between functions

- Passing a map between two functions doesn’t make a copy of the map.

4.4 Summary

- Slices have a capacity restriction, but can be extended using the built-in function

append. - Maps don’t have a capacity or any restriction on growth.

- The built-in function cap only works on slices.

- Passing a slice or map to a function is cheap and doesn’t make a copy of the underlying data structure.

5 Go’s type system

5.1 User-defined types

- Declaration of a struct type:

// user defines a user in the program.

type user struct {

name string

email string

ext int

privileged bool

}- Declaration of a variable of the struct type using a struct literal:

// Declare a variable of type user and initialize all the fields.

lisa := user{

name: "Lisa",

email: "lisa@email.com",

ext: 123,

privileged: true

}- Creating a struct type value without declaring the field names:

// Declare a variable of type user. lisa := user{"Lisa", "lisa@email.com", 123, true} - A second way to declare a user-defined type is by taking an existing type and using it as the type specification for the new type.

- Declaration of a new type based on an int64:

type Duration int645.2 Methods

- The parameter between the keyword

funcand the function name is called areceiverand binds the function to the specified type. When a function has a receiver, that function is called amethod. - There are two types of receivers in Go:

valuereceivers andpointerreceivers. - When you declare a method using a value receiver, the method will always be operating against a copy of the value used to make the method call.

- When you call a method declared with a pointer receiver, the value used to make the call is shared with the method.

- This is a great convenience Go provides, allowing method calls with values and pointers that don’t match a method’s receiver type natively.

5.3 The nature of types

- Does adding or removing something from a value of this type need to create a new value or mutate the existing one? If the answer is create a new value, then use value receivers for your methods. If the answer is mutate the value, then use pointer receivers. This also applies to how values of this type should be passed to other parts of your program.

5.3.1 Built-in types

- Built-in types … as the set of numeric, string, and Boolean types. These types have a primitive nature to them. Because of this, when adding or removing something from a value of one of these types, a new value should be created. Based on this, when passing values of these types to functions and methods, a copy of the value should be passed.

5.3.2 Reference types

- Reference types in Go are the set of slice, map, channel, interface, and function types.

5.3.3 Struct types

- The decision to use a value or pointer receiver should not be based on whether the method is mutating the receiving value. The decision should be based on the nature of the type. One exception to this guideline is when you need the flexibility that value type receivers provide when working with interface values. In these cases, you may choose to use a value receiver even though the nature of the type is nonprimitive.

5.4 Interfaces

5.4.2 Implementation

5.4.3 Method sets

- Method sets as described by the specification:

| Values | Methods Receivers |

|---|---|

| T | (t T) |

| *T | (t T) and (t *T) |

- Method sets from the perspective of the receiver type:

| Methods Receivers | Values |

|---|---|

| (t T) | T and *T |

| (t *T) | *T |

- Listing 5.43 shows the same rules, but from the perspective of the receiver. It says that if you implement an interface using a pointer receiver, then only pointers of that type implement the interface. If you implement an interface using a value receiver, then both values and pointers of that type implement the interface.

- … it’s not always possible to get the address of a value.

- Second look at the method set rules:

| Values | Methods Receivers |

|---|---|

| T | (t T) |

| *T | (t T) and (t *T) |

| Methods Receivers | Values |

|---|---|

| (t T) | T and *T |

| (t *T) | *T |

| * Because it’s not always possible to get the address of a value, the method set for a value only includes methods that are implemented with a value receiver. |

5.5 Type embedding

- Thanks to inner type promotion, the implementation of the interface by the inner type has been promoted up to the outer type.

5.6 Exporting and unexporting identifiers

- When an identifier starts with a lowercase letter, the identifier is unexported or unknown to code outside the package. When an identifier starts with an uppercase letter, it’s exported or known to code outside the package.

- First, identifiers are exported or unexported, not values. Second, the short variable declaration operator is capable of inferring the type and creating a variable of the unexported type. You can never explicitly create a variable of an unexported type, but the short variable declaration operator can.

- Even though the inner type is unexported, the fields declared within the inner type are exported. Since the identifiers from the inner type are promoted to the outer type, those exported fields are known through a value of the outer type.

Concurrency

- Concurrency synchronization comes from a paradigm called

communicating sequential processesor CSP. - The key data type for synchronizing and passing messages between goroutines is called a

channel.

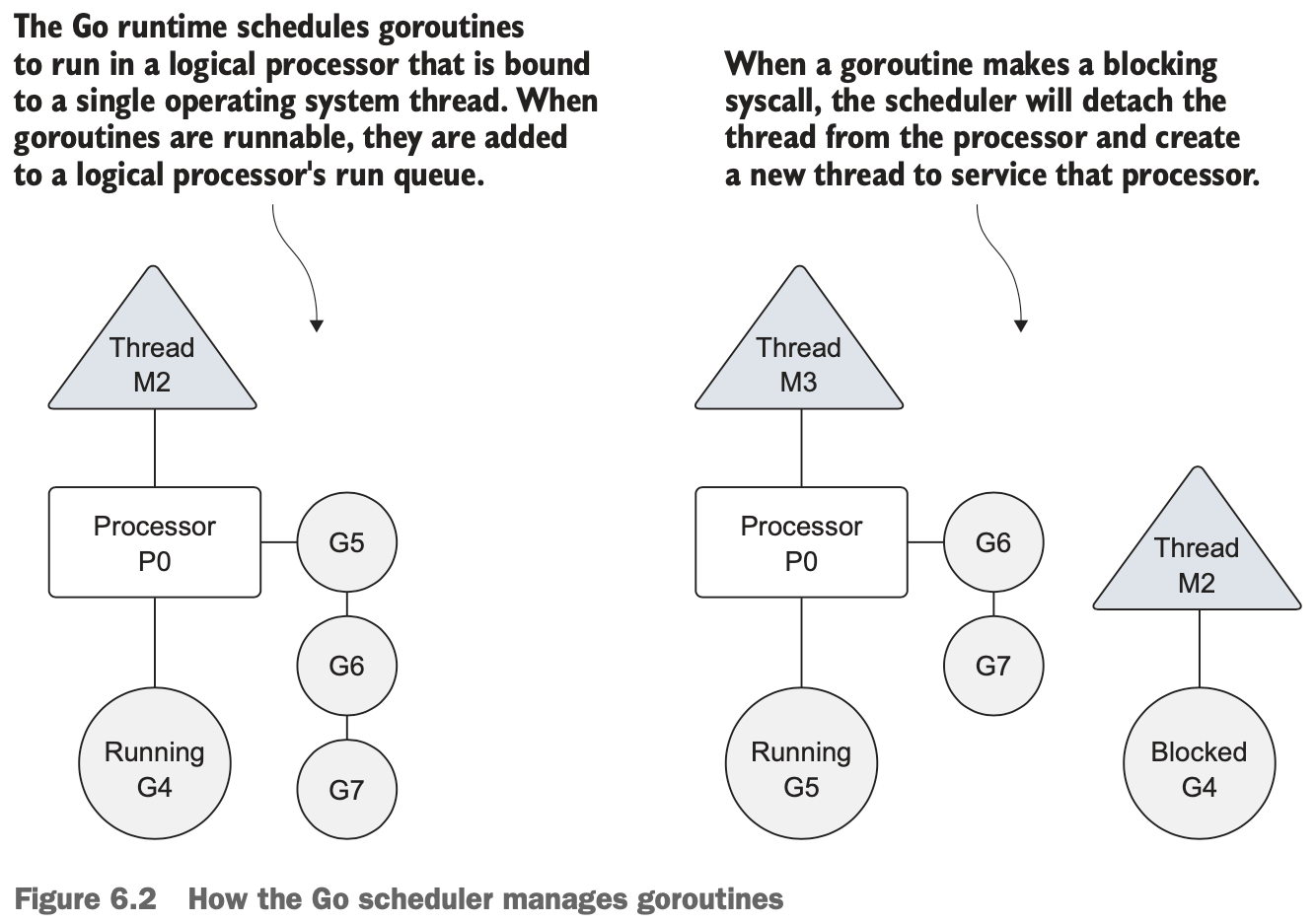

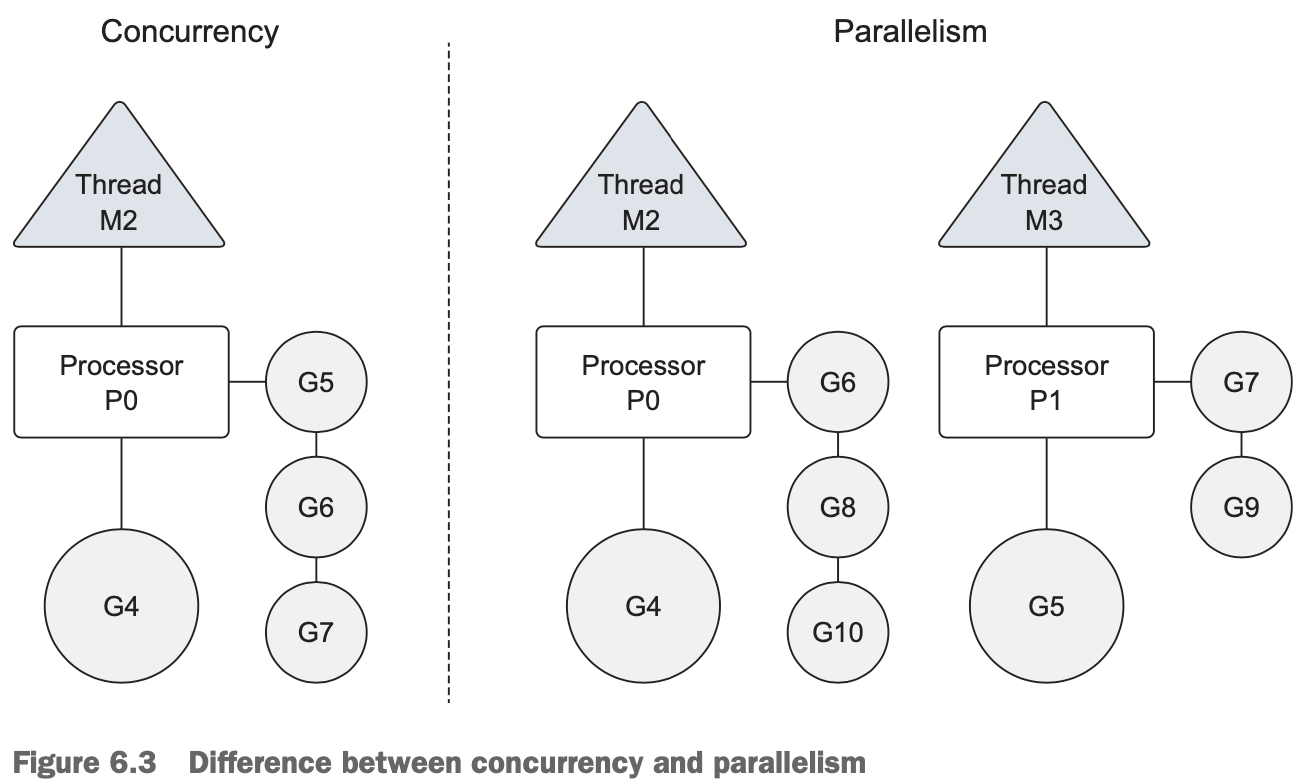

6.1 Concurrency versus parallelism

- There’s no restriction built into the scheduler for the number of logical processors that can be created. But the runtime limits each program to a maximum of 10,000 threads by default. This value can be changed by calling the

SetMaxThreadsfunction from theruntime/debugpackage. If any program attempts to use more threads, the program crashes. - Concurrency is not parallelism. Parallelism can only be achieved when multiple pieces of code are executing simultaneously against different physical processors. Parallelism is about doing a lot of things at once. Concurrency is about managing a lot of things at once. In many cases, concurrency can outperform parallelism, because the strain on the operating system and hardware is much less, which allows the system to do more. This less-is-more philosophy is a mantra of the language.

6.2 Goroutines

GOMAXPROCSfunction from theruntimepackage. This is the function that allows the program to change the number of logical processors to be used by the scheduler. There’s also an environmental variable that can be set with the same name if we don’t want to make this call specifically in our code.- The keyword

deferis used to schedule other functions from inside the executing function to be called when the function returns. - Based on the internal algorithms of the scheduler, a running goroutine can be stopped and rescheduled to run again before it finishes its work. The scheduler does this to prevent any single goroutine from holding the logical processor hostage. It will stop the currently running goroutine and give another runnable goroutine a chance to run.

6.3 Race conditions

// Yield the thread and be placed back in queue.

runtime.Gosched()6.5 Channels

- Using make to create a channel:

// Unbuffered channel of integers.

unbuffered := make(chan int)

// Buffered channel of strings.

buffered := make(chan string, 10)- Sending values into a channel:

// Buffered channel of strings.

buffered := make(chan string, 10)

// Send a string through the channel.

buffered <- "Gopher"- Receiving values from a channel:

// Receive a string from the channel.

value := <-buffered6.5.2 Buffered channels

- A receive will block only if there’s no value in the channel to receive. A send will block only if there’s no available buffer to place the value being sent. This leads to the one big difference between unbuffered and buffered channels: An unbuffered channel provides a guarantee that an exchange between two goroutines is performed at the instant the send and receive take place. A buffered channel has no such guarantee.

- When a channel is closed, goroutines can still perform receives on the channel but can no longer send on the channel.

6.6 Summary

- Atomic functions and mutexes provide a way to protect against race conditions.

- Channels provide an intrinsic way to safely share data between two goroutines.

7 Concurrency patterns

7.1 Runner

Varadic parameterscan accept any number of values that are passed in.

8 Standard library

8.2 Logging

8.2.1 Log package

- The

iotakeyword has a special purpose when it comes to declaring a block of constants. It instructs the compiler to duplicate the expression for every constant until the block ends or an assignment statement is found. Another function of theiotakeyword is that the value ofiotafor each preceding constant gets incremented by 1, with an initial value of 0. Let’s look at this more closely. - Use of the keyword iota:

const (

Ldate = 1 << iota // 1 << 0 = 000000001 = 1

Ltime // 1 << 1 = 000000010 = 2

Lmicroseconds // 1 << 2 = 000000100 = 4

Llongfile // 1 << 3 = 000001000 = 8

Lshortfile // 1 << 4 = 000010000 = 16

...

)- One nice thing about the

logpackage is that loggers are multigoroutine-safe. This means that multiple goroutines can call these functions from the same logger value at the same time without the writes colliding with each other. The standard logger and any customized logger you may create will have this attribute.

8.2.2 Customized loggers

- The

MultiWriterfunction is a variadic function that accepts any number of values that implement theio.Writerinterface. The function returns a singleio.Writervalue that bundles all of theio.Writervalues that are passed in. This allows functions like log.New to accept multiple writers within a single writer.

8.4 Input and output

8.4.1 Writer and Reader interfaces

- Any time the

Readmethod returns bytes, those bytes should be processed first before checking the error value for an EOF or other error value.

9 Testing and benchmarking

- Just like the

go buildcommand, there’s ago testcommand to execute explicit test code that you write.

9.1 Unit testing

9.1.1 Basic unit test

- The Go testing tool will only look at files that end in _test.go.

- A test function must be an exported function that begins with the word

Test. Not only must the function start with the wordTest, it must have a signature that accepts a pointer of typetesting.Tand returns no value.

9.1.4 Testing endpoints

- … the package name also ends with

_test. When the package name ends like this, the test code can only access exported identifiers. This is true even if the test code file is in the same folder as the code being tested.

9.2 Examples

- Examples are based on existing functions or methods. Instead of starting the function with the word

Test, we need to use the wordExample. - To determine if the test succeeds or fails, the test will compare the final output of the function with the output listed at the bottom of the example function.

- handlers_example_test.go:

// Use fmt to write to stdout to check the output.

fmt.Println(u)

// Output:

// {Bill bill@ardanstudios.com}- The

Output: marker is used to document the output you expect to have after the test function is run.

9.3 Benchmarking

- Benchmark functions begin with the word

Benchmarkand take as their only parameter a pointer of typetesting.B. - It’s important to place all the code to benchmark inside the loop and to use the

b.Nvalue. If this isn’t done, the results can’t be trusted. - Another great option you can use when running benchmarks is the

-benchmemoption. It will provide information about the number of allocations and bytes per allocation for a given test.

留言