Chapter 1. Introduction

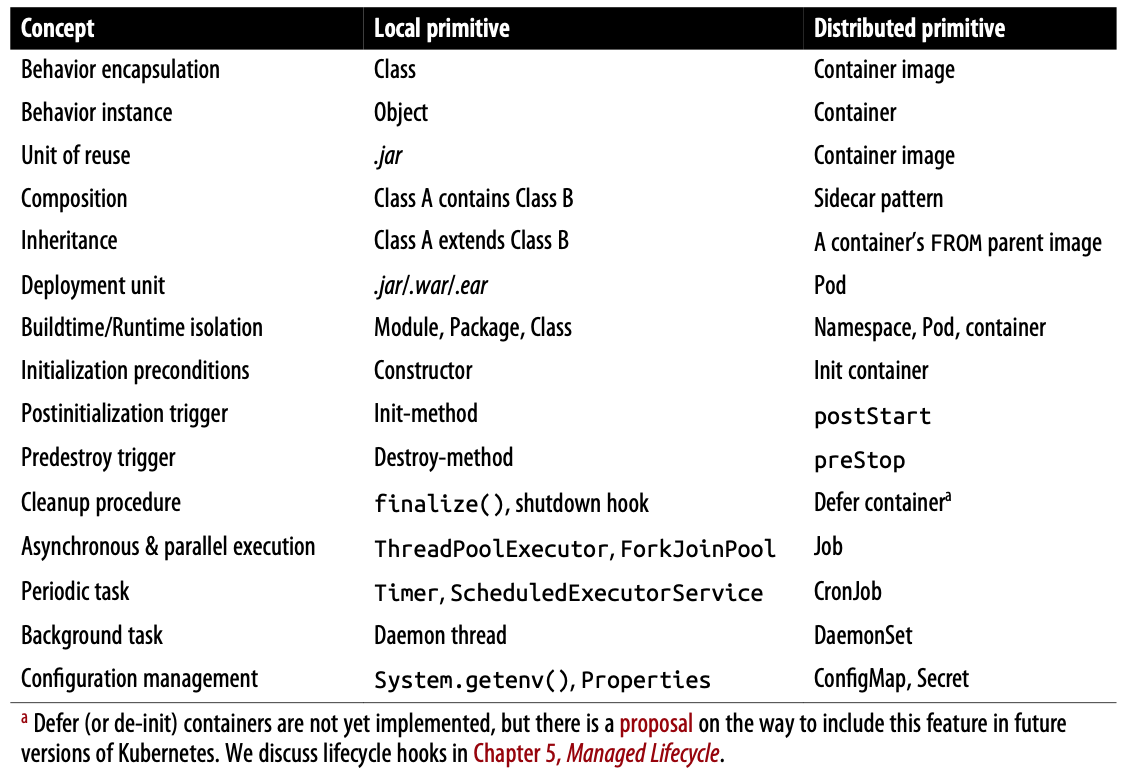

Distributed Primitives

- Local and distributed primitives

Annotations

- Another primitive very similar to labels is called annotations. Like labels, annotations are organized as a map, but they are intended for specifying nonsearchable metadata and for machine usage rather than human.

- So while labels are used primarily for query matching and performing actions on the matching resources, annotations are used to attach metadata that can be consumed by a machine.

Part I. Foundational Patterns

Chapter 2. Predicatable Demands

Solution

Pod Priority

- Here comes the critical part. If there are no nodes with enough capacity to place a Pod, the scheduler can preempt (remove) lower-priority Pods from nodes to free up resources and place Pods with higher priority.

- The Kubelet first considers QoS and then PriorityClass of Pods before eviction.

Project Resources

- LimitRange allows setting resource usage limits for each type of resource. In addition to specifying the minimum and maximum permitted amounts for different resource types and the default values for these resources, it also allows you to control the ratio between the requests and limits, also known as the overcommit level.

Chapter 3. Declarative Deployment

Solution

Bule-Green Release

- A Blue-Green deployment needs to be done manually if no extensions like a Service Mesh or Knative is used, though.

Chapter 4. Health Probe

Solution

Readiness Probes

- Rather than restarting the container, a failed readiness probe causes the container to be removed from the service endpoint and not receive any new traffic.

- It is also useful for shielding the service from traffic at later stages, as readiness probes are performed regularly, similarly to liveness checks.

- While process health checks and liveness checks are intended to recover from the failure by restarting the container, the readiness check buys time for your application and expects it to recover by itself. Keep in mind that Kubernetes tries to prevent your container from receiving new requests (when it is shutting down, for example), regardless of whether the readiness check still passes after having received a SIGTERM signal.

Discussion

- Apart from logging to standard streams, it is also a good practice to log the reason for exiting a container to

/dev/termination-log. This location is the place where the container can state its last will before being permanently vanished.

Chapter 5. Managed Lifecycle

Solution

Poststart Hook

- The

postStartaction is a blocking call, and the container status remainsWaitinguntil thepostStarthandler completes, which in turn keeps the Pod status in thePendingstate. This nature ofpostStartcan be used to delay the startup state of the container while giving time to the main container process to initialize.

Chapter 6. Automated Placement

Solution

Placement Policies

- Consider that in addition to configuring the policies of the default scheduler, it is also possible to run multiple schedulers and allow Pods to specify which scheduler to place them. You can start another scheduler instance that is configured differently by giving it a unique name. Then when defining a Pod, just add the field

.spec.schedulerNamewith the name of your custom scheduler to the Pod specification and the Pod will be picked up by the custom scheduler only.

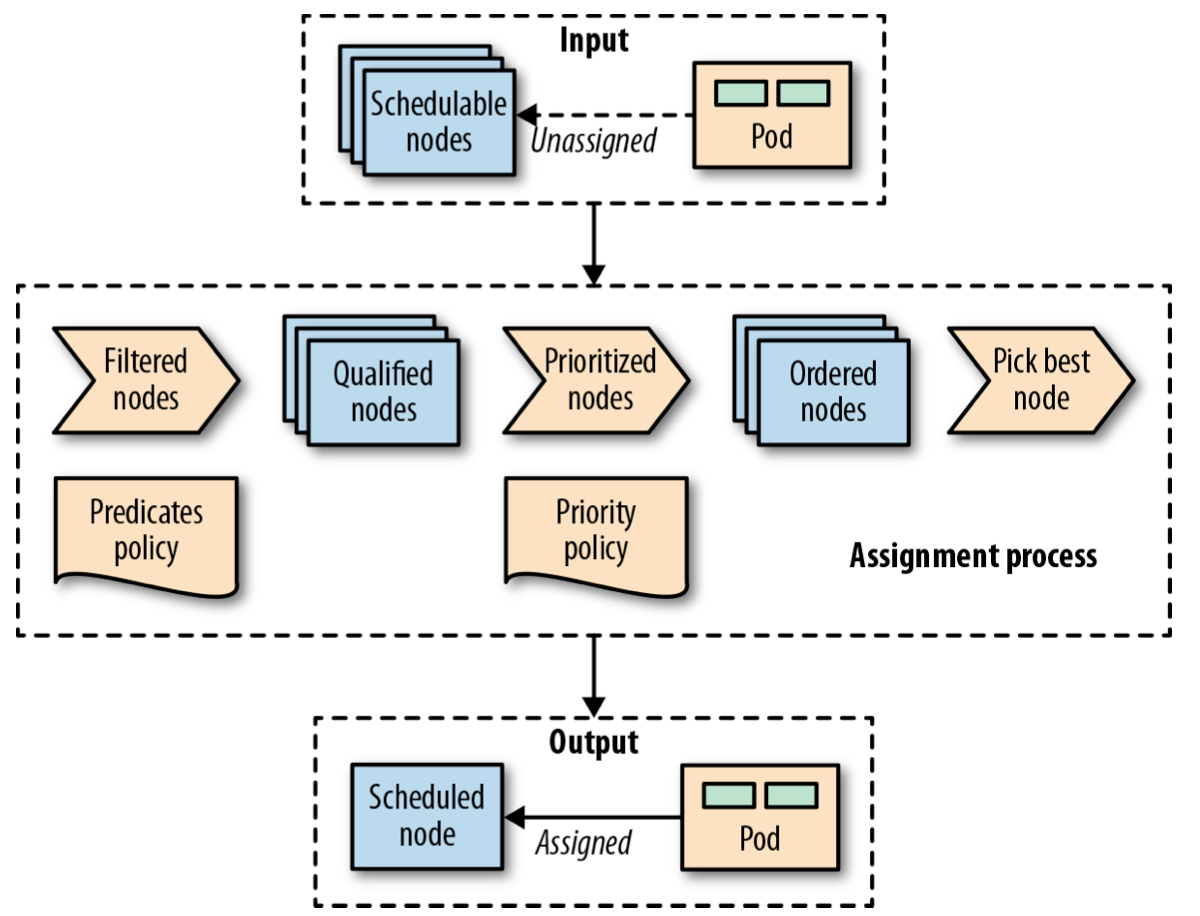

Scheduling Process

- A Pod-to-node assignment process

- As soon as a Pod is created that is not assigned to a node yet, it gets picked by the scheduler together with all the available nodes and the set of filtering and priority policies. In the first stage, the scheduler applies the filtering policies and removes all nodes that do not qualify based on the Pod’s criteria. In the second stage, the remaining nodes get ordered by weight. In the last stage the Pod gets a node assigned, which is the primary outcome of the scheduling process.

Taints and Tolerations

- There are hard taints that prevent scheduling on a node (

effect=NoSchedule), soft taints that try to avoid scheduling on a node (effect=PreferNoSchedule), and taints that can evict already running Pods from a node (effect=NoExecute). - Once a Pod is assigned to a node, the job of the scheduler is done, and it does not change the placement of the Pod unless the Pod is deleted and recreated without a node assignment. As you have seen, with time, this can lead to resource fragmentation and poor utilization of cluster resources. Another potential issue is that the scheduler decisions are based on its cluster view at the point in time when a new Pod is scheduled. If a cluster is dynamic and the resource profile of the nodes changes or new nodes are added, the scheduler will not rectify its previous Pod placements. Apart from changing the node capacity, you may also alter the labels on the nodes that affect placement, but past placements are not rectified either.

- All these are scenarios that can be addressed by the descheduler. The Kubernetes descheduler is an optional feature that typically is run as a Job whenever a cluster administrator decides it is a good time to tidy up and defragment a cluster by rescheduling the Pods. The descheduler comes with some predefined policies that can be enabled and tuned or disabled. The policies are passed as a file to the descheduler Pod, and currently, they are the following:

- RemoveDuplicates

- LowNodeUtilization

- RemovePodsViolatingInterPodAntiAffinity

- RemovePodsViolatingNodeAffinity

- Regardless of the policy used, the descheduler avoids evicting the following:

- Critical Pods that are marked with

scheduler.alpha.kubernetes.io/criticalpodannotation. - Pods not managed by a ReplicaSet, Deployment, or Job.

- Pods managed by a DaemonSet.

- Pods that have local storage.

- Pods with PodDisruptionBudget where eviction would violate its rules.

- Deschedule Pod itself (achieved by marking itself as a critical Pod).

- Critical Pods that are marked with

Part II. Behavioral Patterns

Chapter 9. Daemon Service

Solution

- By default, a DaemonSet places one Pod instance to every node. That can be controlled and limited to a subset of nodes by using the

nodeSelectorfield. - A Pod created by a DaemonSet already has

nodeNamespecified. As a result, the DaemonSet doesn’t require the existence of the Kubernetes scheduler to run containers. That also allows using a DaemonSet for running and managing the Kubernetes components. - Pods created by a DaemonSet can run before the scheduler has started, which allows them to run before any other Pod is placed on a node.

- Since the scheduler is not used, the

unschedulablefield of a node is not respected by the DaemonSet controller. - Pods managed by a DaemonSet are supposed to run only on targeted nodes, and as a result, are treated with higher priority and differently by many controllers. For example, the descheduler will avoid evicting such Pods, the cluster autoscaler will manage them separately, etc.

Chapter 10. Singleton Service

Solution

Out-of-Application Locking

- If ReplicaSets do not provide the desired guarantees for your application, and you have strict singleton requirements, StatefulSets might be the answer.

- However, such a Service is still useful because a headless Service with selectors creates endpoint records in the API Server and generates DNS A records for the matching Pod(s). With that, a DNS lookup for the Service does not return its virtual IP, but instead the IP address(es) of the backing Pod(s). That enables direct access to the singleton Pod via the Service DNS record, and without going through the Service virtual IP. For example, if we create a headless Service with the name

my-singleton, we can use it asmy-singleton.default.svc.cluster.localto access the Pod’s IP address directly. - To sum up, for nonstrict singletons, a ReplicaSet with one replica and a regular Service would suffice. For a strict singleton and better performant service discovery, a StatefulSet and a headless Service would be preferred.

Chapter 11. Stateful Service

Solution

Networking

- For example, if our random-generator Service belongs to the default namespace, we can reach our

rg-0Pod through its fully qualified domain name:rg-0.random-generator.default.svc.cluster.local, where the Pod’s name is prepended to the Service name. This mapping allows other members of the clustered application or other clients to reach specific Pods if they wish to. - We can also perform DNS lookup for SRV records (e.g., through

dig SRV random-generator.default.svc.cluster.local) and discover all running Pods registered with the StatefulSet’s governing Service.

Other Features

- Partitioned Updates: … By using the default rolling update strategy, you can partition instances by specifying a

.spec.updateStrategy.rollingUpdate.partitionnumber. The parameter (with a default value of 0) indicates the ordinal at which the StatefulSet should be partitioned for updates. If the parameter is specified, all Pods with an ordinal index greater than or equal to the partition are updated while all Pods with an ordinal less than that are not updated. That is true even if the Pods are deleted; Kubernetes recreates them at the previous version. This feature can enable partial updates to clustered stateful applications (ensuring the quorum is preserved, for example), and then roll out the changes to the rest of the cluster by setting the partition back to 0. - Parallel Deployments: When we set

.spec.podManagementPolicyto Parallel, the StatefulSet launches or terminates all Pods in parallel, and does not wait for Pods to become running and ready or completely terminated before moving to the next one. If sequential processing is not a requirement for your stateful application, this option can speed up operational procedures.

Chapter 12. Service Discovery

Solution

Internal Service Discovery

- Session affinity: When there is a new request, the Service picks a Pod randomly to connect to by default. That can be changed with sessionAffinity: ClientIP, which makes all requests originating from the same client IP stick to the same Pod. Remember that Kubernetes Services performs L4 transport layer load balancing, and it can not look into the network packets and perform application-level load balancing such as HTTP cookie-based session affinity.

- Choosing ClusterIP: During Service creation, we can specify an IP to use with the field

.spec.clusterIP. It must be a valid IP address and within a predefined range. While not recommended, this option can turn out to be handy when dealing with legacy applications configured to use a specific IP address, or if there is an existing DNS entry we wish to reuse.

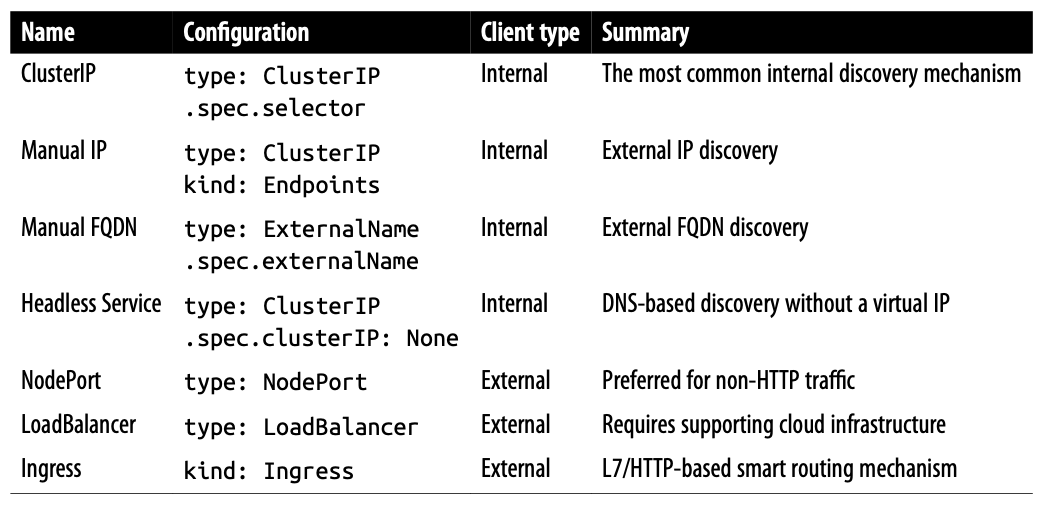

Discussion

- Service Discovery mechanisms

Chapter 13. Self Awareness

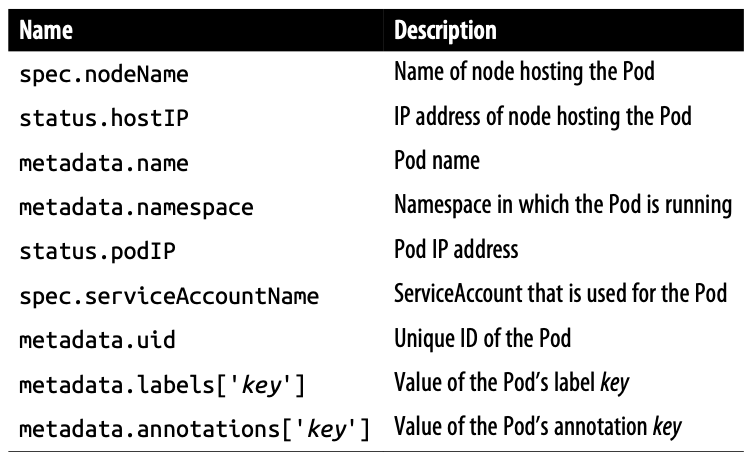

Solution

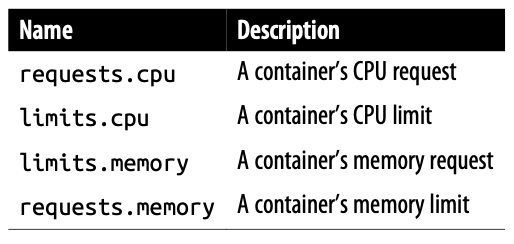

- Downward API information available in fieldRef.fieldPath

- Downward API information available in resourceFieldRef.resource

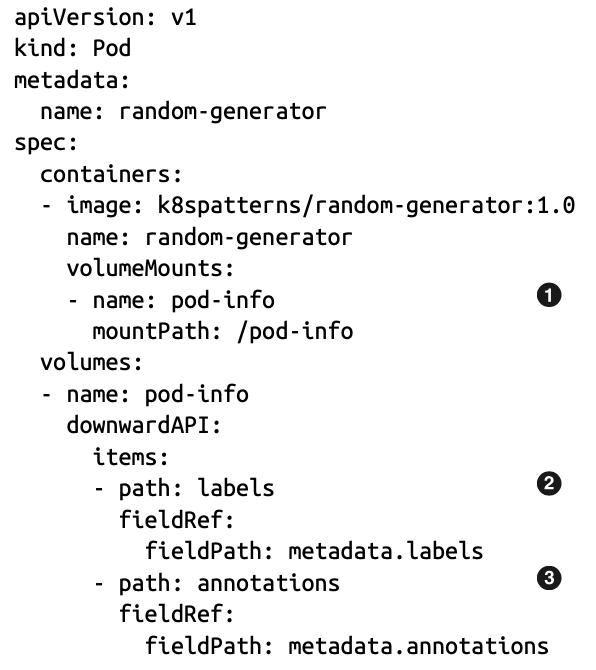

- A user can change certain metadata such as labels and annotations while a Pod is running. Unless the Pod is restarted, environment variables will not reflect such a change. But downwardAPI volumes can reflect updates to labels and annotations.

- Downward API through volumes

- Values from the Downward API can be mounted as files into the Pod.

- The file labels contain all labels, line by line, in the format name=value. This file gets updated when labels are changing.

- The annotations file holds all annotations in the same format as the labels.

- With volumes, if the metadata changes while the Pod is running, it is reflected in the volume files. But it is still up to the consuming application to detect the file change and read the updated data accordingly. If such a functionality is not implemented in the application, a Pod restart still might be required.

Part III. Structural Patterns

Chapter 14. Init Container

Solution

- More Initialization Techniques: A few other related techniques used to initialize Kubernetes resources are different from init containers and worth listing here for completeness:

- Admission controllers: … This plugin system is not very flexible, which is why admission webhooks were added to Kubernetes.

- Admission webhooks: … There are two types of admission webhooks: the mutating webhook (which can change resources to enforce custom defaults) and the validating webhook (which can reject resources to enforce custom admission policies).

- Initializers

- PodPresets: PodPresets are evaluated by another admission controller, which helps inject fields specified in a matching PodPreset into Pods at creation time.

- … init containers is for developers deploying on Kubernetes, whereas the techniques described here help administrators control and manage the container initialization process.

Part IV. Configuration Patterns

Chapter 21. Configuration Template

Problem

- … there is a limit on the sum of all values of ConfigMaps or Secrets, which is 1 MB (a limit imposed by the underlying backend store Etcd).

Part V. Advanced Patterns

Chapter 22. Controller

Solution

- From an evolutionary and complexity point of view, we can classify the active reconciliation components into two groups:

- Controllers: A simple reconciliation process that monitors and acts on standard Kubernetes resources. More often, these controllers enhance platform behavior and add new platform features.

- Operators: A sophisticated reconciliation process that interacts with CustomResourceDefini tions (CRDs), which are at the heart of the Operator pattern. Typically, these Operators encapsulate complex application domain logic and manage the full application lifecycle.

- Labels … are indexed in the backend database and can be efficiently searched for in queries.

- A limitation of labels is that only alphanumeric names and values with restrictions can be used.

- Annotations are not indexed, …

- Preferring annotations over labels for arbitrary metadata also has the advantage that it does not negatively impact the internal Kubernetes performance.

- Note the

watch=truequery parameter in Example 22-2. This parameter indicates to the API Server not to close the HTTP connection but to send events along the response channel as soon as they happen (hanging GET or Comet are other names for this kind of technique). The loop reads every individual event as it arrives as a single item to process.

Chapter 23. Operator

Problem

- Custom resources, together with a Controller acting on these resources, form the Operator pattern.

Solution

Example

- Awesome Operators has a nice list of real-world operators that are all based on the concepts covered in this chapter.

- If you are looking for an operator written in the Java programming languages, the Strimzi Operator is an excellent example of an operator that manages a complex messaging system like Apache Kafka on Kubernetes. Another good starting point for Java-based operators is the JVM Operator Toolkit, which provides a foundation for creating operators in Java and JVM-based languages like Groovy or Kotlin and also comes with a set of examples.

Chapter 24. Elastic Scale

Solution

Horizontal Pod Autoscaling

- Deployments create new ReplicaSets during updates but without copying over any HPA definitions. If you apply an HPA to a ReplicaSet managed by a Deployment, it is not copied over to new ReplicaSets and will be lost. A better technique is to apply the HPA to the higher-level Deployment abstraction, which preserves and applies the HPA to the new ReplicaSet versions.

Vertical Pod Autoscaling

- Update policy: Controls how VPA applies changes. The Initial mode allows assigning resource requests only during Pod creation time but not later. The default Auto mode allows resource assignment to Pods at creation time, but additionally, it can update Pods during their lifetimes, by evicting and rescheduling the Pod. The value

Offdisables automatic changes to Pods, but allows suggesting resource values. This is a kind of dry run for discovering the right size of a container, but without applying it directly. updateMode: Off: The VPA recommender gathers Pod metrics and events and then produces recommendations. The VPA recommendations are always stored in the status section of the VPA resource. However, this is how far theOffmode goes. It analyzes and produces recommendations, but it does not apply them to the Pods. This mode is useful for getting insight on the Pod resource consumption without introducing any changes and causing disruption. That decision is left for the user to make if desired.

Cluster Autoscaling

- Kubernetes Cluster Autoscaler (CA)

- While HPA and VPA perform Pod-level scaling and ensure service capacity elasticity within a cluster, CA provides node scalability to ensure cluster capacity elasticity.

Scaling Levels

- You can also go one step further and use techniques and libraries such as Netflix’s Adaptive Concurrency Limits library, where the application can dynamically calculate its concurrency limits by self-profiling and adapting.

留言